Understanding the behavior of breakpoints in Xcode

02 Jul 2018I’ve long accepted that breakpoints in Xcode move in ‘mysterious ways’. Some won’t hit while they should and others seemingly hit multiple times before execution continues. Over the years I built a mental model that explained some of the unpredictable behavior, but I mainly relied on frequent Xcode restarts and pressing Continue a lot. I only recently learned that Xcode actually provides all information needed to understand and predict how breakpoints will behave. It’s all right there in the Breakpoint navigator (⌘ + 6).

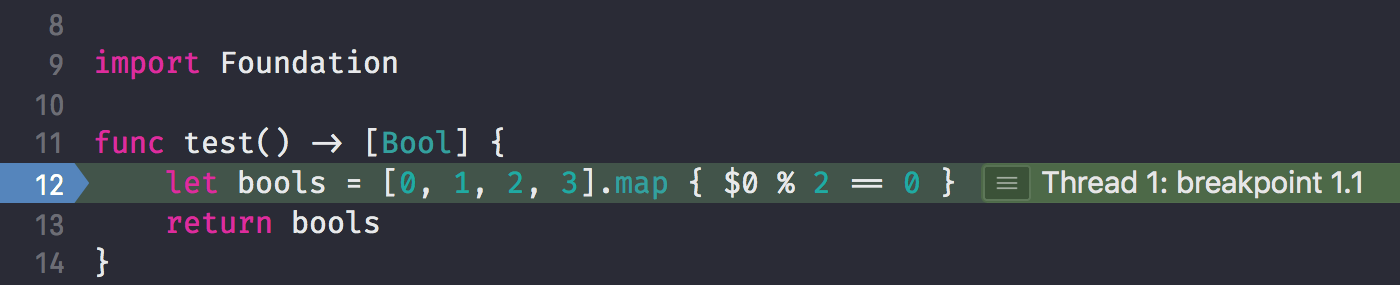

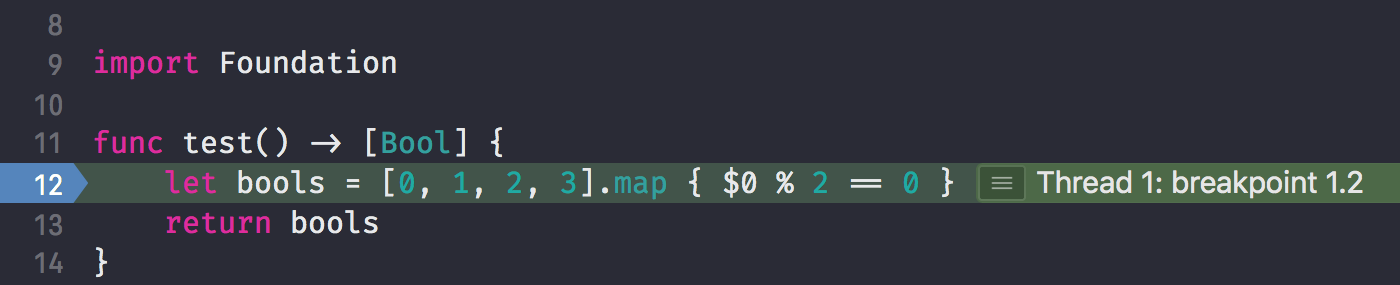

Let’s first look at breakpoints that seem to hit multiple times. I had already built up enough of a mental model to know that a breakpoint on the following line would hit multiple times:

let bools = [0, 1, 2, 3].map { $0 % 2 == 0 }

It indeed does hit multiple times, five times to be precise. This can be understood if we first recognize that the line consists of two statements. The assignment to bools is one, and the contents of the map closure is another. The breakpoint hits for the first time when the program arrives at the first statement. The next four hits are for each invocation of the map closure.

I’ve taught myself to distinguish between the hitted statements by looking at the variables view in Xcode’s debug area. The presence of a $0 in this case would indicate that execution stopped at the statement inside the closure. If I wasn’t sure, I would temporarily rewrite my code like so:

let bools = [0, 1, 2, 3]

.map {

$0 % 2 == 0

}

That would allow me to put a breakpoint on line 1 and 3 and have each of them only hit on their corresponding statements. If you’re thinking that there must be better way, you’re right and there is.

If we carefully look at the instruction pointer appearing in the editor while execution is suspended for the first hit versus the remaining four hits, we can notice one small but significant difference:

For the first hit, the instruction pointer indicates it breaked at breakpoint 1.1. For the other hits, it shows breakpoint 1.2. The changing number after the dot signifies that the same breakpoint hit at a different statement, or ‘location’ in LLDB parlance. The first digit is assigned to a breakpoint when we add it to the debugger. Once added, the debugger will resolve the breakpoint to locations in the executable program. The resolving step is necesary because when we add a breakpoint by clicking in the gutter of the editor, it is added based on a filename and line number in our source code. The result is a set of one, multiple (as we’ve seen above) or no locations in the executable where any part of that line of source code is executed.

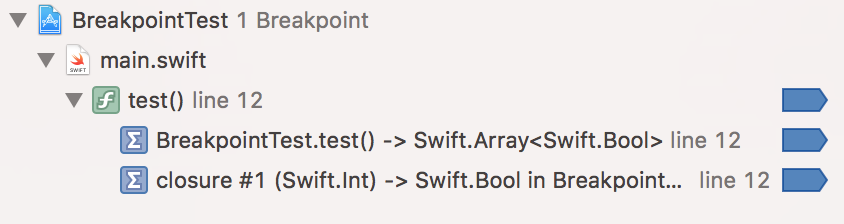

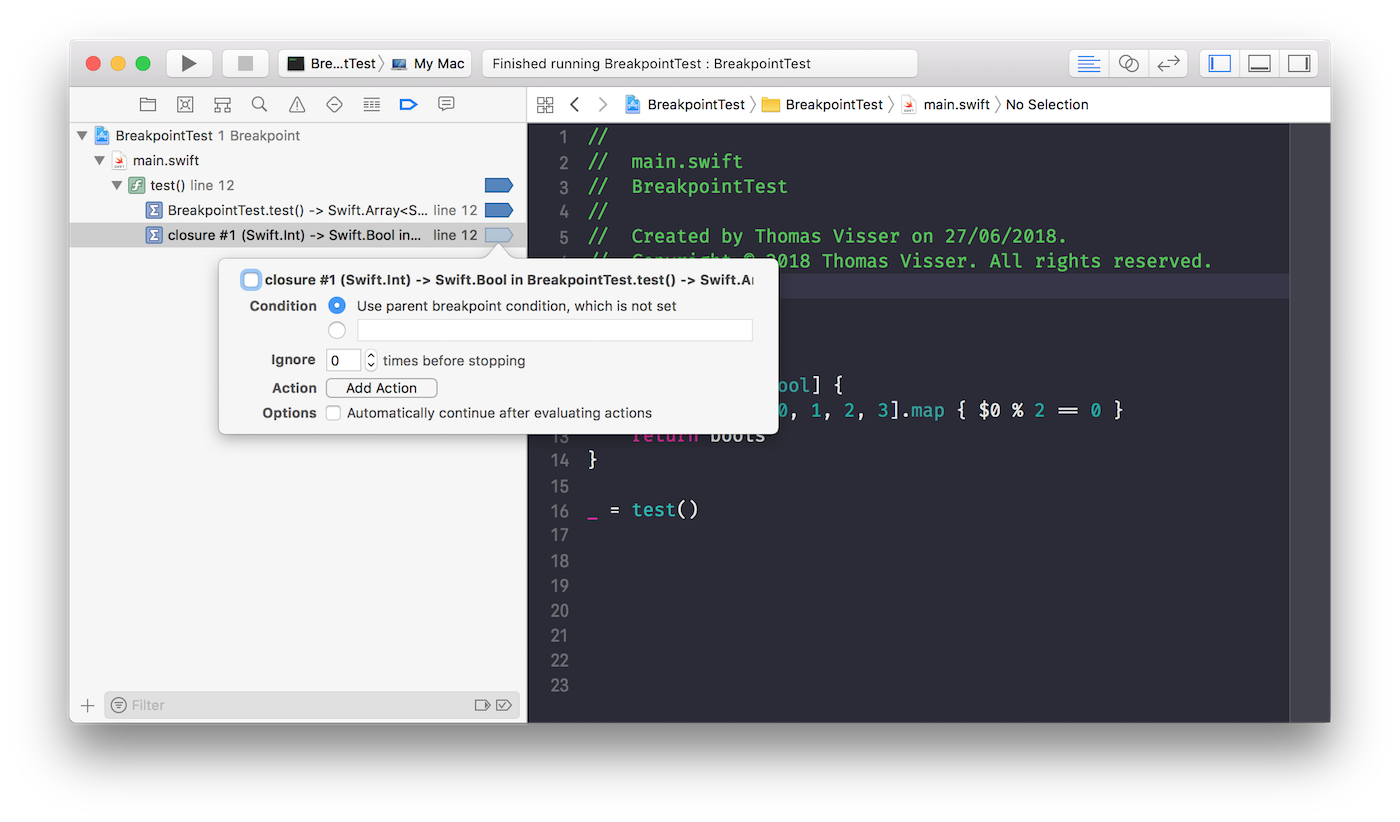

Xcode actually shows the resolved locations of breakpoints in the Breakpoint navigator. You can tap on the disclosure arrow next to a breakpoint to reveal them:

You can configure the behavior of each location individually or disable one alltogether. This allows you to fine-tune your breakpoints and provide a more focussed debugging experience.

What to do if a breakpoint is not hitting at all? Go to the Breakpoint navigator to see if that breakpoint has a disclosure arrow. If not, it failed to resolve any locations that the debugger can suspend execution on. That breakpoint will not hit. Whenever this happens to me, I check if syntax highlighing is broken in the editor of the file that contains the breakpoint. A clear indication that ‘something is wrong’. Closing the editor (Ctrl + ⌘ + w) and re-opening the file usually fixes it, but as always, your mileage may vary.

Epilogue

Judging by older screenshots, the Breakpoint navigator hasn’t always shown the resolved locations. I don’t know when it was added, my guess would be around the time Swift support was added, but I only noticed a few months ago. I went looking for it after being triggered by how breakpoints are added in Android Studio: when clicking in the gutter for a line with multiple statements, it’ll ask you which statement you want to add the breakpoint for. I think that makes a lot of sense. Breaking on every statement in a line is rarely what you’re trying to achieve.